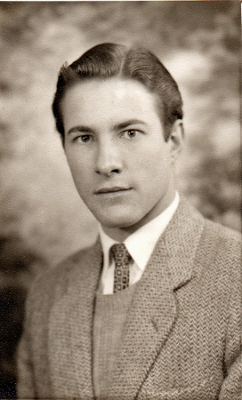

Michael Davies in 1950. He was 23 at the time,

and a recent convert from a Protestant background.

Traditional Catholics seem to be few and spread our in our age -- but

they are actually many and vibrant in large clusters spread in much of

the world. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, instead, their most

prominent leaders could fill at most a large van, and all the faithful

would not fill more than a few additional buses...

In those days of violent repression and unjust persecution, while

modernists were free to do what they pleased, after the advent of Pope

Paul VI's new rite, the Traditional Rites of the Latin Church were

considered "forbidden" and "ab-rogated" for all intents and purposes,

and those who dared offer them and attend them were condemned to either

disdain or ignominy on a level that it would be hard to fully comprehend

today. Because while we are persecuted relentlessly, there are many

islands of peace and tranquility, and we are many more than they were.

They were few -- but they were great. Most were in Europe, a few in the

United States, a couple in Australia and South America or elsewhere --

two bishops in all, out of thousands around the world, and hundreds of

conservative Fathers of the Council. How can we ever repay them? The

least we can do, other than prayers and Masses for their souls, is to

remember them.

Michael Davies was one of those handful of giants, one of the few

Traditional Catholic laymen to have mightily influenced the course of

events with his writings that, even more so in those pre-internet days,

were essential to make many perplexed Catholics aware that they were not

alone, and that their utter confusion before what they had been

witnessing since the Council was perfectly rational and shared by many.

Davies would also serve as a longtime president of the International Una

Voce Federation (1995-2003). He died 10 years ago, in September 2004.

But the justice for which he fought would be accomplished by the Pope

elected on the following year with the publication of Summorum

Pontificum and its recognition that the traditional Roman Rite of the

Mass, "was never ab-rogated," because, "what earlier generations held as

sacred, remains sacred and great for us too, and it cannot be all of a

sudden entirely forbidden or even considered harmful" (Letter to

Bishops).

|

Davies in 2003, in a meeting with the Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, Card. Joseph Ratzinger |

________________________________________

A characteristic of the Protestant innovations is that in both doctrine and liturgy they were imposed from above by clerics backed by the support of those holding civil power. There was little enthusiasm for the changes among the mass of the Faithful and sometimes fierce opposition! Commenting on the introduction of Cranmer's first (1549) Prayer Book the Anglican Dean of Bristol, Douglas Harrison, admits: "It is not surprising that it met with a reception which was nowhere enthusiastic, and in the countryside there was violent opposition both in East Anglia and in Devon and Cornwall, where ten thousand 'stout and valiant personages' marched on Exeter demanding their old services in Latin."

In order not to over-alarm the

Faithful, the first Protestant Communion Services tended to be interim

measures, ambiguous rites which could pave the way for more radical

revisions to be introduced at a more opportune moment. To assist in

this purpose the basic structure and many of the prayers of the Roman

Mass were retained where possible, sometimes even in Latin.

"To build up a new liturgy from the very

foundation was far from Luther's thoughts. . . . He preferred to make

the best use of the Roman Mass, for one reason, as he so often insists,

because of the weak, i.e. so as not to needlessly alienate the people

from the new Church by the introduction of novelties. From the ancient

rite he merely eliminated all that had reference to the sacrificial

character of the Mass. The Canon for instance, and the preceding

Offertory. He also thought it best to retain the word 'Mass'." Mgr.

Hughes has this to say concerning the transformation of religious life

in Saxony: "That the Mass must go because the Mass was a blasphemy was

one certain first principle. But since, as Melanchthon said, 'the world

is so much attached to the Mass that it seems impossible to wrest people

from it', Luther wished that the outward appearance of the service

should be changed as little as possible. In this way the common people

would never become aware there was any change, said Luther, and all

would be accomplished 'without scandal'. 'There is no need to preach

about this to the laity.' Even the communion was to be given under one

species only to those who would otherwise cease to receive the

Sacrament. Forms and appearances were comparatively unimportant, and in

the later years Luther could say 'Thank God . . . our churches are so

arranged that a layman, an Italian say, or a Spaniard, who cannot

understand our preaching, seeing our Mass, choir, organs, bells etc.

would surely say . . . there is no difference between it and his own.' "

Needless to say, although the other reformers began their revolutions

with interim, ambiguous rites, the difference between their finalised

services and the Mass would quickly have been apparent to any layman

familiar with the former rite.

Like Luther, Cranmer included the word

"Mass" in the description of his 1549 communion service: "The Supper of

the Lorde and the Holy Communion, commonly called the Masse."

The Spaniard, Francis Dryander [Francisco

de Enzinas], writing to the Zurich Protestants from Cambridge concerning

this service remarked: "I think, however, that, by a resolution not to

be blamed, some puerilities have still been suffered to remain, lest the

people should be offended by too great an innovation. These, trifling

as they are, may shortly be amended." On the same 'puerilities' Bucer

explains that these things " . . . are to be retained only for a time,

lest the people, not having learned Christ, should be deterred by too

extensive innovation from embracing his religion."

Dr. Darwell Stone writes that "it is

probable that the Prayer Book of 1549 represented rather what it was

thought safe to put out at the time than what Archbishop Cranmer and

those who were acting with him wished, and that at the time of the

publication of the book they already had in view a revision which would

approach much more nearly the position of the extreme Reformers." Canon

E. C. Ratcliff makes the same observation: "Its promoters regarded it as

an interim measure preparing the way for a more accurate embodiment of

their reforming opinions." The general policy of Cranmer and his friends

was "to introduce the Reformation by stages, gradually preparing men's

minds for more radical courses to come. At times compulsion or

intimidation was necessary in order to quell opposition, but their

general policy was first to neutralise the conservative mass of the

people, to deprive them of their Catholic-minded leaders, and then

accustom them by slow degrees to the new religious system. Cranmer

accordingly deplored the incautious zeal of men like Hooper, which would

needlessly provoke the conservatives and stiffen the attitude of that

large class of men who, rightly handled, could be brought to acquiesce

in ambiguity and interim measures." Thus in England, as in Germany, "in

the first reformed liturgy, while there was a resolute expunging of

references to the offering of Christ in the sacrament, much remained to

the scandal of the more uncompromising of the Reformers."

Many of the clergy "endeavoured to make

the best of an evil situation, and used the new communion service as

though it were the same as the ancient Mass, which, of course, it was

never intended to be." This happened to such an extent that Bucer

complained: "The Last Supper is in very many places celebrated as the

Mass, so much indeed that the people do not know that it differs beyond

that the vernacular tongue is used."

...

A final principle of the Reformers was

that there was no necessity for liturgical uniformity among the

different churches. They maintained that a diversity of rite,

traditions, ordinances and policies may exist among the churches. Such

diversity "doth not dissolve and break the unity which is one God, one

faith, one doctrine of Christ and His sacraments, preserved and kept in

these several churches without any superiority or pre-eminence that one

church by God's law may or ought to challenge over another." As Cranmer

made clear, once the Reformers were in a position to enforce their new

services they were far more insistent upon the need for uniformity than

the Catholic Church had ever been. Needless to say, the Catholic Church

had never insisted on absolute liturgical uniformity-----far from it.

The various authorised rites within the Church were allowed to keep

their own customs, rituals and liturgical languages without interference

from Rome. Even within the Latin rite itself there was a degree of

pluriformity in that there were differing usages, or in other words, not

independent rites but variants of the Roman rites. The Dominican or

Sarum Missals provide examples. ...[T]hese usages within the Latin rite

did not differ from the Missal of St. Pius V on any important point. What

the Reformers were trying to justify in their demand for pluriformity

was the right to take an unprecedented step in the history of

Christendom, the right to concoct new services. This in itself would

have been a complete break with tradition-----up to this point the

liturgy had developed by a process of natural evolution. Some

ceremonies and prayers were gradually discarded as the centuries passed,

for example the Bidding Prayers or the practice of having two lessons

before the Gospel. Others were added, such as the Last Gospel. Any

attempt to bring about a clear break with any traditional usage should

automatically arouse the suspicions of the orthodox, even if ostensibly

plausible motives are adduced for doing so.

Michael Davies

Cranmer's Godly Order

1976

No comments:

Post a Comment