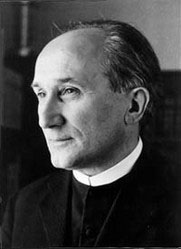

Guy Noir, who sent this to me, tells me that he remains a fan of Romano Guardini (perhaps similarly an odd match, he says, like his admiration for Louis Bouyer who was doctoral advisor to Hans Kung), even if he detects in him shadows of a Nouvelle Theologie of which he is not a fan (in reading his The Last Things,

Guy Noir, who sent this to me, tells me that he remains a fan of Romano Guardini (perhaps similarly an odd match, he says, like his admiration for Louis Bouyer who was doctoral advisor to Hans Kung), even if he detects in him shadows of a Nouvelle Theologie of which he is not a fan (in reading his The Last Things,Nevertheless, with those remarks, he sends along this helpful excerpt by Romano Guardini, "The Last Judgement in Revelation," Living Bulwark, Vol. 55 (December 2011):

Near the end of his life, during his last visit to Jerusalem, Jesus spoke these words:[Hat tip to JM]“And immediately after the tribulation of those days, the sun shall be darkened and the moon shall not give her light, and the stars shall fall from heaven, and the powers of heaven shall be moved. And then shall appear the sign of the Son of Man in heaven; and then shall all tribes of the earth mourn; and they shall see the Son of Man coming in the clouds of heaven with much power and majesty. And he shall send his angels with a trumpet, and a great voice: and they shall gather together his elect from the four winds, and from the farthest parts of the heavens to the utmost bounds of them.” (Matthew 24:29-31)If we shake off the seeming familiarity which comes from having heard them often, these passages strike us suddenly as strange and disconcerting. This is not how we should expect things to be. Here premises are taken for granted to which we are not sure we can give assent. But if we have some acquaintance with revelation, and know enough of men to treat certain of their unconscious assumptions with caution—and these are the first steps in Christian knowledge—it is this very feeling that here is something disconcerting that alerts us to the fact that we are face to face with an essential and crucial element in our faith. The disconcerting element here lies in the concrete, the personal approach.

And again: “When the Son of Man shall come in his majesty, and all the angels with him, then shall he sit upon the seat of his majesty. And all nations shall be gathered together before him, and he shall separate them one from another, as the shepherd separates the sheep from the goats. And he shall set the sheep on his right hand, but the goats on his left. Then shall the King say to them that shall be on his right hand: ‘Come, blessed of my Father, possess the kingdom prepared for you from the foundation of the world. For I was hungry, and you gave me to eat; I was thirsty, and you gave me to drink; I was a stranger, and you took me in; naked, and you covered me; sick, and you visited me; I was in prison, and you came to me.’ Then shall the just answer him, saying: ‘Lord, when did we see you hungry, and feed you; thirsty, and gave you drink? And when did we see you a stranger, and take you in? Or naked, and cover you? Or when did we see you sick, or in prison, and come to you?’ And the King answering, shall say to them: ‘Amen I say to you, as long as you did it to one of these, my least brethren, you did it to me.’

And then he shall say to them also that shall be on his left hand: ‘Depart from me, you cursed, into the everlasting fire which was prepared for the Devil and his angels. For I was hungry, and you gave me not to eat; I was thirsty, and you gave me not to drink. I was a stranger, and you took me not in; naked, and you covered me not; sick and in prison, and you did not visit me.’ Then they also shall answer him, saying: ‘Lord, when did we see you hungry, or thirsty, or a stranger, or naked, or sick, or in prison, and did not minister to you?’ Then he shall answer them, saying: ‘Amen, I say to you, as long as you did it not to one of these least, neither did you do it unto me.’ And these shall go into everlasting punishment, but the just into life everlasting.” (Matthew 25:31-46)

Habit of the modern mind

The habit of the modern mind is to take seriously only that kind of thinking that interprets everything in terms of natural necessity or of intellectual laws. Existence for us has become a system of matter and energy, of law and natural order. Every process takes place within that system. Children or simple folk may think of natural objects as being manipulated by superior beings, as they are in legends and fairy tales, but the educated adult does not. For him the first condition of intelligent thinking is to conceive of the universe as an interconnection of physical and spiritual laws, which govern man and his destinies as well as the historical process.

If a final judgment is posited—a procedure, that is, by which the life and deeds of man are scrutinized, judged, and given their eternal value—we would have to think of it as a judgment in which man, or more properly his spirit, comes into the unveiled light of God, and in that light, his life becomes transparent, and his worth is made evident.

Christ comes as judge

In Jesus’ discourse on the Last Judgment, however, this is not at all what takes place. The judge is not an abstract deity, an all-wise, all-righteous spirit, but Christ, the Son made man. Nor does man, by the mere fact of his death, or the world, simply by coming to an end, appear before God. Rather, it is Christ who “comes.” He comes to the world and wrests it from a condition in which “this-sidedness” and the subjection to natural law make possible the obscurity of history. A final investigation is carried out which brings all existing things into the presence of Christ. Men, not only their spirits, appear before him—men in their concrete, soul-and-body actuality; and not individual men only, but “the world.” In order to make this possible, the body—the deceased, corrupt body—rises up from the dead, not by any natural necessity, but in obedience to the summons of Christ. And the act of judgment is not simply illumination in the eternal light and holiness of God, but an act of Jesus Christ, who was once upon earth and now reigns in eternal glory. He reviews mankind in its whole history, as well as each particular man, passes judgment, and assigns to each man that form of being which accords with his worth in the sight of God.

Sheer fantasy or myth?

To modern man, all this appears as sheer fantasy—at best as symbol. To his mentality, this kind of thinking is on the level of children and primitives. Mythology, folklore, and fairy tales treat universal processes in this anthropomorphic manner, that is, as modeled on human conduct. Children, as soon as they grow up, and primitive people, when they become civilized, perceive that the universe is governed by inflexible laws and must be conceived of in philosophical or scientific terms. The Christian teaching of the Last Judgment is just a myth and must give way to a more serious and advanced view of reality.

A direct intervention in human history

Again we have to decide where we stand with regard to revelation. Are we to confine our faith to our emotions, and adapt our thinking to that of current views, or shall we be Christians in our minds also? For what modern man describes as childish, primitive, and anthropomorphic is the essential, distinguishing quality of our faith. For when the worth of the world and of history are finally determined, it will not be by universal natural or spiritual laws, nor by confrontation with an absolute, divine reality, but by a divine act. Let it be well understood—by an act, and not through the workings of some force of nature or spirit, just as the economy of salvation does not rest upon some higher natural order but upon a direct intervention of God, which takes place in the sphere of human history and finds constant expression in this sphere; and just as the world did not evolve as a natural reality from natural causes, but as God’s work, summoned into being by his free and all-powerful word.

If we want to be Christians in our thinking also, then we cannot conceive of the relation of God to the world, to man, and to the whole of existence in terms derived from natural science or metaphysics, but only in concepts belonging to the personal sphere; that is, precisely in the despised anthropomorphic concepts of action, decision, destiny, and freedom. Such is the language of Scripture, and when a man has striven for truth with sufficient sincerity and above all with sufficient patience for false notions to fall away and things to show themselves in their true light, he comes to see that in the final sifting of values, what really meets the case are those so-called anthropomorphic concepts.

A sign of contradiction

The judgment is the last in the series of God’s acts. It proceeds from his free counsels, and is carried out by him whose intervention in history was rejected by men at his appearance upon earth, but whose destiny, since God is faithful, accomplished our redemption. Throughout history, he has remained as a “sign that will be contradicted,” (Luke 2:34) as the touchstone for men and for nations. It is he who executes the judgment. He is doing it because he is God’s Son, because he is the Word “through whom all things were made,” (John 1:3) and to whom the world belongs, whether the world acknowledges it or not.

How does God’s judgment take place?

The strangeness which reverses our scientific and philosophic notions reaches still deeper. How does this judgment take place? On what is it based, and according to what standards does it determine a man’s worth?

At first glance we might assume that what is judged would be a man’s actions and omissions, his deeds as well as his character, the details as much as the whole, each according to the multiplicity of rules and norms pertaining to it. Instead, we see everything fused into only one thing: love—the love that is aroused by compassion for man’s need. And what is here in question is plainly that first and greatest commandment, and the second which is like unto it, as Jesus taught in the Gospel, the commandment of love, of which the apostle speaks as of “the fulfilling of the law” (Matthew 24:37-39; Romans 13:10). Consequently, although it is only the love for one’s neighbor that is mentioned, the commandment includes the whole realm of love; only love is spoken of, but this love includes doing and becoming and being what is right.

To love Christ

How will this standard of love be established and applied? The judge, we might suppose, would say, “You have obeyed the law of love and are therefore accepted,” or, “You have denied the law of love, and are therefore rejected.” What he says, however, is, “You are accepted because you have shown love to me; you are rejected because you denied me love.” This, too, is comprehensible, we might answer, since love is the first commandment and should be practiced toward all men, and since Christ, who enjoins this commandment and fulfilled it himself to the uttermost, has placed himself, as it were, behind each man to lend final weight to each individual being.

The highest standard of love

This might well be so, but once we examine the context without bias, we find that this is not what Christ teaches. The highest standard of love is not the love Christ preaches and to which all are obligated, including Christ himself; the highest standard of love is Christ himself. It begins in him and persists through him. Outside of Christ, it is nonexistent, and philosophical disquisitions on the subject have as little to do with this kind of love as he who in the New Testament is called the Father has to do with “the divinity of the heavenly sphere” or the concept of “cause and effect” has to do with God’s providence.

The Christian meaning of judgment

Now there opens before us the uniqueness, the awesomeness and, yes, the scandal of the Christian meaning of judgment: man will be judged according to his relationship to Christ. Truthfulness, justice, faithfulness, chastity, and whatever else is considered ethical are in their deepest meaning the right relationship to Christ. If we speak of truth, we imply a general attitude of the mind, namely, the fact that we recognize something in the light of eternal reality. But in the prologue to his Gospel, John gives us to understand that this interpretation of truth is but an interpolated, conditional link. Ultimately, truth is the Word, the Logos himself, and knowledge, accordingly, is knowing the Logos, Christ, and all things in him.

The same applies to judgment. If we speak of goodness, we imply the highest value; and by right conduct, we understand the realization of good. But according to the discourse on the Last Judgment, Christ is the good, and to do good means to love Christ. Truth and goodness, in the final analysis, are no mere abstract values and concepts, but someone—Jesus Christ. Reversing the approach, we might say that every intimation of truth, however fragmentary, is also the beginning of a knowledge of Christ. Similarly, any charitable action is directed toward Christ, and reaches him in the end, just as any wicked action, whatever its immediate context, is, in the end, an attack upon him. Goodness may shine out in various places, in man, things, and events; but in its essence it shines forth Jesus Christ. The doer need have no thought of Christ; he may think of other people only, but his act ultimately reaches Christ. He need not even know Christ and may never have heard of him, yet what is done is done to Christ.

The fulfillment of redemption

To pierce with his glance the width of the whole world and the course of thousands of years, the life of each man and of each nation and community, to judge and affix to each the meaning it bears eternally, is God’s act of doom. Christ will come and execute that judgment. It will be irrevocable because it is true, because it is the exact account without remainder of every man, every community of men. It is irrevocable also because it is an act of power as much as of truth, power that is absolute and irresistible. By this judgment the state of man and of mankind will be settled before God forever.

But Christ is not only Judge; he is also Redeemer. Even as Judge he is Redeemer. The judgment is not the revenge of the offended Son of God, not his personal triumph over his enemies. By saying that truth and goodness are a person—Christ—it is not suggested that any personal element would intrude and blur the impartial validity of truth and goodness. The judgment is justice, yet not justice in and for itself, but justice bound up with the living mind and love of Christ. The Last Judgment is the fulfillment of redemption.

Greater than history

The vastness of such a view of things is overwhelming. It disrupts and reverses modern thinking and its conception of existence as the expression of natural law or a philosophical system. It is not ideas and laws that matter, but reality. The most real of realities is a person, the Son of God made man. He is what he was, Jesus of Nazareth. But he will be manifest as Lord, mightier than the world, greater than history, and more comprehensive than all that is called idea, value, or moral law. These things exist and are valid, but only as rays from his light.

Seeing Christ in everything

The doctrine of the Last Judgment is, at bottom, a revelation of Christ. It shows us, too, the task which confronts us if we want to be Christians in the true sense of the word. It implies seeing Christ in everything, carrying his image in our hearts with such intensity that it lifts us above the world, above history and the works of men, and enables us to see those things for what they are, to weigh them and assign to them their eternal value—in a word, to be their judges.

3 comments:

I used to love Guardini -- until the day, around the time of my conversion, where I first read reports of his often-repeated "new-style" masses for students still in the 1920s/30s in Berlin. Versus populum, chairs in circle, etc, etc.

Sorry, I can't take that. The errors of Germany, why didn't an Apparition warn us about those !?...

Good point, NC. I've often wondered about the question you put at issue: how much time should we spend looking for the good fruit on a tree that also produces some very bad apples?

Do you use the early Schillebeeckx work on ecclesiology in as a text in your class because it makes some very good points, or do you discard it altogether as water from a poisoned well?

I haven't spent much time on Guardini or on many of the Nouvelles. A little on Henri de Lubac, perhaps. I prefer the classics. St. Thomas. Even Garrigou-Lagrange.

Guardini's "The Lord" remains a favorite of mine, and several other pieces have been of personal help. But I laughed out lout at "The errors of Germany," since I have thought the same myself countless times.

As for "Versus populum, chairs in circle," and the like, I think there was a real struggle early in the 1900s to break away from the inevitable dead ritualism that can't help but rise and fall around orthodoxy in a successful Church culture. Guardini and others to my mind found their original impetus there. The later wild windows that blew through open windows... that is another story entirely in my book.

But a successful theological and liturgical orthodoxy does bring with some inevitable triumphalism and comfortableness that "we're Catholic, so we're OK, period." And salvation by osmosis is risky belief. Although I am by no means a big George Weigel fan [I returned mhy own copy of E.C.!} I think that is what he senses as well in this linked discussion, in which I find some merit:

http://www.firstthings.com/blogs/firstthoughts/2014/05/evangelicals-catholics-and-togetherness

Post a Comment