Thomas F. Bertonneau, "World Without Men: The Forgotten Novel of Totalitarian Lesbiocracy by Charles Eric Maine" (The Brussels Journal, August 17, 2010):

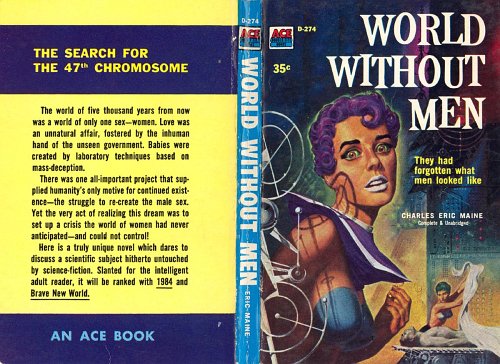

The blurb on the thirty-five cent Ace paperback likens Charles Eric Maine’s 1958 novel World Without Men[Hat tip to F.R.]to George Orwell’s 1984 and Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World. Ordinarily – and in consideration of the genre and the lurid cover – one would regard such a comparison skeptically. Nevertheless, while not rising to the artistic level of the Orwell and Huxley masterpieces, World without Men merits being rescued from the large catalogue of 1950s paperback throwaways, not least because of Maine’s vision of an ideological dystopia is based on criticism, not of socialism or communism per se nor of technocracy per se, but rather of feminism. Maine saw in the nascent feminism of his day (the immediate postwar period) a dehumanizing and destructive force, tending towards totalitarianism, which had the potential to deform society in radical, unnatural ways. Maine grasped that feminism – the dogmatic delusion that women are morally and intellectually superior to men – derived its fundamental premises from hatred of, not respect for, the natural order; he grasped also that feminism entailed a fantastic rebellion against sexual dimorphism, which therefore also entailed a total rejection of inherited morality.

* * * * * * *

The crumbling Ace paperback of Maine’s novel from which I quote contains a Publisher’s Postscript. It reads in part as follows: “While the manuscript of WORLD WITHOUT MEN was being prepared for publication, the staff of Ace books were startled to see… a story in the New York Times, for Oct. 16, 1957. This told of the announcement at a meeting of a ‘planned parenthood’ society of advanced work on a ‘synthetic steroid tablet’ to be taken orally to create a limited period of sterility.” According to the Postscript, this story and one other “unexpectedly underline the credibility of Charles Eric Maine’s novel.” About Maine himself, information remains scarce. Charles Eric Maine was the penname of David McIlwain (1921 – 1981), who served in the Royal Air Force in World War Two and became a writer after the war. He seems to have published fourteen novels, most of them, to judge by their titles, in the science fiction genre. (Apart from World Without Men I have read none of them.) An early effort, Spaceways (1953) became a film under the same name the year after its publication.

2 comments:

Occasionally a "conservative" science fiction work like this shows up. I remember "Love Conquers All" by Fred Saberhagen in the early 70's -- perhaps the only anti-abortion science fiction novel ever written. But they are anomalies. Science fiction is basically fiction about science. The people who write it are basically geeks in love with science. They are propagandists for science. Masturbatory tributes to science are their revenge for not having made the high school football team.

Even the "dystopian" science fiction novels usually oppose science with some phony opponent like "better" science, science in league with magic, etc. When religion, especially the hierarchical, ecclesiastical sort, opposes science in fiction, it automatically becomes Galileo vs. the Inquisition. That should tell you all you need to know about science fiction.

As a young man who did not play on the high school footbal team (baseball, and not very well), I developed a taste for science fiction and read a boxful of those old Ace double-sided novels in the sixties. They provided a clunky counter harmony to V2 and the general degradation of the times. There were a few very good writers among the many hacks -- Phillip K Dick, Robert Silverberg, Thomas M Disch -- but not a recognizably Catholic or even Christian viewpoint among them.

The genre does attract some Christian writers -- C.S. Lewis wrote three works of science fiction, and Walter Miller's A Canticle for Leibowitz is unmistakably Catholic. Though a children's novel, Madeleine L'Engle's A Wrinkle in Time would be another example.

Post a Comment