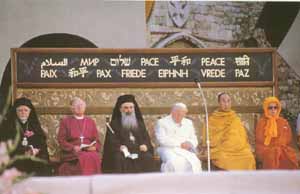

Zenit.org reported on September 7, 2006, that a Peace Appeal was issued at the International Meeting of Prayer for Peace, held in Assisi on Monday and Tuesday, September 4th and 5th, 2006. The appeal, it said, was signed by hundreds of representatives of various religions. Sandro Magister reports at

www.chiesa (September 11, 2006), in the body of a post entitled, "

Benedict XVI Has Become a Franciscan," that Pope Benedict declined to put in an appearance at the interreligious meeting at Assisi as Pope John Paul II had done in 1986 and 2002. Yet Magister also reports, in a section of his post entitled "Restorations also underway for the interreligious meetings," on how Benedict, in his September 2nd address to the bishop of Assisi, is attempting to sort out the way for continued interreligious dialogue without the confusions that accompanied the Assisi summits of the previous pontificate. Whether or not he will succeed in this remains to be seen. While his cautions against religious 'relativism' are clear enough, he may not avoid other pitfalls suggested in the article below.

Given the recent anniverasary of the Assisi meetings, and given the recent interest in some of the commentary (in recent comboxes) in the problems posed by the Assisi meetings in 1986 and 2002, I thought it opportune to share what I have found to be the most cogent discussion of the arguments against the Assisi adventure that I have seen. Let me say from the outset that I consider John Paul II to be in many ways an outstanding and excellent pope. I don't think it's only my bias as a professional academician or philosopher coming through here, or the fact that he is the only pope in history with two earned doctorates, one in theology, the other in philosophy, or that he was an excellent and well-known phenomenologist long before becoming Pontiff. His many encyclicals attest to his magisterial acumen and gifts as a teacher. The orthodoxy of his formal magisterial office is, I think, beyond question. This, however, does not place him, in his prudential judgments, above reproach. The following are difficult things to confront. But they must be confronted, if we are not to bury our heads in the sand. Read, pray, discern, and see what you think with the Mind of the Church and the Mind of Christ.

John Paul II and Assisi: Reflections of a "Devil's Advocate"

by Father Brian W. Harrison, O.S.(Part I: "... more or less good and praiseworthy")

Now that the cause for beatification of the late Holy Father John Paul II has been officially opened by the successor in the See of Peter, an open, public and honest discussion of his long and epoch-making pontificate, marked by a calm and serious evaluation of its possible weaknesses as well as its undoubted strengths, has become not only opportune but also necessary. For the long-standing tradition of the Church is that no Servant of God may be raised to the honors of the altar before both sides of the question -- that is, testimonies both for and against his or her sanctity -- are first heard and taken into due consideration.

Since Vatican Council II, the specific role of a priest investigator who was popularly styled "Devil's Advocate" for each cause for canonization has been abolished in the proceedings of the Vatican Congregations for Saints' Causes. The substantial

functions of this fabled official, however, are still required to be carried out in one way or another by those in charge of evaluating the life of each Servant of God. In the spirit of this requirement of Holy Mother Church -- though not without a certain trepidation -- I shall therefore make so bold as to offer in this two-part article some critical observations about one of the recently deceased Pontiff's most audacious initiatives: his convocation of the inter-religious gatherings at Assisi in 1986 and 2002. In considering my own remarks (which will be based exclusively on the late Pope's public statements and actions), I ask readers to bear in mind that they are made in full consciousness and appreciation of John Paul II's many monumental qualities, contributions and achievements in world affairs as well as in his leadership of the Church. Those qualities and achievements I by no means wish to deny, but rather, take for granted, in what follows.

Actions that Speak Louder than WordsIn the April 2002 issue of

Inside the Vatican a letter of mine was published registering respectful but firm disagreement with Pope John Paul II's convocation of the second interreligious "Day of Prayer" for peace at Assisi (January 24, 2002). Among other things, I observed that this and the similar 1986 papal initiative at Assisi were tending to send the message (denounced by Pope Pius XI in his 1928 encyclical

Mortalium Animos as erroneous and perilous) "that all religions are more or less good and praiseworthy." After all, when one publicly invites people as guests to one's own home turf, welcoming them there for the precise purpose of displaying certain of their wares, or carrying out certain of their own distinctive activities which have been agreed upon in advance, will not the average observer assume that such wares and/or activities are considered by the host of this event to be -- at least in general terms -- laudable and meritorious? (Why would he have hosted it at all if he thought otherwise?)

I was soon taken to task by one reader who asserted that even if some observers drew such negative conclusions from Assisi, "it would only prove that [they] had found an occasion [of scandal] in an act which they did not understand correctly, in spite of all the explanations that had been given: a case of scandal of the weak bordering on Pharisaical scandal." Which explanations? My critic referred to two papal allocutions of October 1986 regarding Assisi I, and another about interreligious dialogue in general of 19 May 1999. These allocutions, he assured me, were sufficient to acquit John Paul II of any charge of giving scandal. They covered all the bases.

Well, I shall proceed to explain why I honestly don't think the Holy Father really

did cover all the bases in those allocutions. But I would first raise the questions as to whether, even supposing these authoritative explanations did remove any

objective grounds for scandal, that would, in itself, be enough to justify the Assisi gatherings. I think not. For Sacred Scripture teaches that we should avoid even innocent but unnecessary, actions under circumstances where they are liable to give scandal to weak or ignorant brethren. (Look it up: I Cor. 10:27-29.) And were Assisi I and II really necessary (in spite of two previous millennia of church history in which no Successor of Peter had ever done anything remotely similar)? I don't believe Pope John Paul himself ever tried to claim these pan-religious prayer-fests were

necessary. He just clearly considered them

opportune.

It is also worth remarking that I was not merely concerned about Assisi's probably effects on

Catholics. My published letter said that "the practical effect [of Assisi] in the minds of millions of observers worldwide can only have been to create or reinforce the impression that the Roman Catholic Church now endorses" the aforesaid idea condemned by Pius XI. In the light of my critic's appeal to certain

papal documents, the distinction between observers in general and

Catholic observers is important. For it is clearly much more incumbent on Catholics than on non-Catholics to read official Church documents and to form their opinions in the light of such teachings. Therefore, even if my critic were right about the said papal documents, that would still miss the main point. For my objection to Assisi also had in mind the vast,

non-Catholic majority of ordinary people round the world) not to mention merely huge numbers of merely nominal Catholics), who cannot realistically be expected to spend time in libraries searching for authentic pontifical texts in

L'Osservatore Romano. As was entirely foreseeable, the opinions of the masses concerning these religious 'spectaculars' were formed mainly by the accounts furnished in secular radio, newspaper, and television coverage.

Indeed, my main objection to Assisi is the resulting

misleading public witness as to the Church's true position. Scandal has been given not only to those who, because of Assisi, have been led to believe (or confirmed in their existing belief) that "all religions are more or less good and praiseworthy." Scandal has also been given to all those who, while personally rejecting that benign appraisal of "all religions," have been misled into thinking that Roman Catholicism now officially endorses it. It is all too likely that the Assisi gatherings have made conversion to Catholicism more difficult than ever for devout, conservative Protestant and Eastern Orthodox believers, as well as for traditional Jews and Muslims. Many such 'unecumenicized' non-Catholics -- holding vastly differing convictions among themselves but sharing a common abhorrence for religious liberalism -- were aghast or even contemptuous at what they saw happening at Assisi.

The Papal Explanations of AssisiWe must now go on to ask whether in fact the papal allocutions cited by my critic really even claim to reassure Catholics (and others) that the error rebuked by Pope Pius XI is not implied by the Assisi gatherings.

Of course, a number of authoritative post-conciliar Church documents, regarding Assisi and other ecumenical and interreligious activities, clearly assert that such forms of dialogue and collaboration do not involve, and are not intended to imply, such errors as

indifferentism,

syncretism, or

relativism. (1)

Syncretism is the mixing together of elements from Christianity with those of non-Christian religions, or a reductionist search for unity through a 'lowest common denominator' approach. (2)

Indifferentism is the view that any given religion is basically just as good (or bad) as any other. And (3)

relativism holds (along very similar lines to indifferentism) that there are no absolute or universal religious truths, so that one religion can be true or right for one culture or historical period, while other religions (or no religion at all) may be right for other cultures or periods.

By appealing to statements of John Paul II dissociating Vatican-approved interreligious activity from these three errors, my critic left the impression that I had accused the Pope of promoting one or more of them at Assisi. But this is not true. [1] My complaint, let me repeat, was that Assisi in effect promoted a different error -- less extreme than the three just mentioned, but still grave -- to wit, the view that "all religions are more or less good and praiseworthy" (in Pius XI's precise words, "plus minus bonas ac laudabiles"). It is of course quite possible, and indeed, very common, to hold this opinion without embracing the cruder (indifferentist) error that all religions are

equally good and praiseworthy -- or perhaps equally bad and blameworthy. (The fact that all participants at the Olympic Games are "more or less world-class athletes" does not, of course, imply that they are all

equally competent.)

Moreover, it is not simply a question of this one statement of Pius XI. That some religions are definitely not

plus minus bonas ac laudabiles is an infallible teaching of the Church's ordinary Magisterium. For that is the plan meaning of the First Commandment. There are many religious cults, including some represented at Assisi I and II, which are not merely deficient or inadequate, but downright

bad. They are, objectively, intrinsically idolatrous, and therefore morally bad in their very essence. According to both Old and New Testaments, the "gods" of the pagans are really devils: cf. Psalm 96:5 and I Cor. 10:20. The

Catechism of the Catholic Church recognizes this objective evil. Under the bold-type heading "Idolatry," it teaches: "The first commandment condemns

polytheism. It requires man neither to believe in, nor venerate, other divinities than the one true God" (No. 2112). Now, if "the Great Thumb," an entity invoked by an African shaman at Assisi in 1986, is

not one of these "other divinities" whose idolatrous cult is, according to the Catechism "condemned" by God, then it is hard to imagine what conceivable cult

would ever qualify for such condemnation. (The official Vatican publication for Assisi I, entitled

World Day of Prayer for Peace, includes the text of this prayer to "the Great Thumb." [2]

Now, in the papal allocutions which my critic appeals to, did Pope John Paul dissociate his own interreligious initiatives from the aforesaid error condemned by Pius XI (along with the whole of Scripture and Tradition)? Not even once, I am afraid. On the contrary, his statements themselves

even tend to suggest the self-same error!

The first of the three was John Paul's Wednesday allocution of October 22, 1986, several days before Assisi I. It seems to me that this discourse fully confirms the deep concern expressed in my published letter. To begin with, the Pope spoke euphemistically, even disingenuously. He repeatedly reassured the pilgrims in St. Peter's Square that the purpose of the interreligious gathering the following Monday was to be "prayer to God," the "the Divinity," and even to "the living God." Its purpose, he said, was to be that of "invoking from God" the gift of peace, "imploring from God" that gift, and so on. To listen to these words, one would think that only monotheists -- worshippers of the one true God -- had been invited. Could it be that the Holy Father himself felt a certain uneasiness, a certain need to sugar-coat the Assisi pill, when addressing a large audience of ordinary, devout Catholics?

In this allocution, the Pope's only expression of reserve regarding non-Christian religions was very mild, and was in any case immediately buried under copious and reassuring words of praise. He said, "We recognize the limits of those religions, but that in no way negates the fact that they contain religious values and qualities -- sometimes outstanding ones." [3] Elsewhere in the allocution the Pope praises the fasts, penitences, and "pilgrimages to sacred places" practiced by non-Christians, and affirms that all their religions "are called to contribute to the birth of a world that is more human, more just, more fraternal." [4] But what evidence from Scripture or Tradition is there that God really "calls" pagan and polytheistic religions, as such, to that kind of noble, humanitarian mission? Are we not taught rather that God simply wills their demise? And that His "call" to their followers is, rather, to abandon their grievous errors in order to worship the true God in the true religion? John Paul added that we should have "sincere respect" for these "other religions" (i.e., for the religions

as such, not just for the

persons who practice them in good faith), as well as respect for "[their] prayer." He also mentioned the planned afternoon session wherein Christians were going to listen to the prayers of the non-Christians, but without joining in. And what was the rationale for this non-participation? To show Christian

disapproval of polytheistic or pantheistic prayer, perhaps? Not at all. Quite the contrary. "In this way," the Pope explained, 'we manifest our respect for the prayer of others and for their attitude before the Divinity." [5]

Certainly, the Pope also clearly and repeatedly proclaimed in this discourse that Christ is the only Savior. But that of course is irrelevant to the point at issue. What interests us here is whether there was any indication in this discourse that some of the religions to be represented at Assisi might not be "more or less good and praiseworthy." And the answer is crystal clear: Not a trace. For it is plain that even something which admittedly has its "limits" can still merit that description.

Similar comments can be made about John Paul II's statements on the day of Assisi I itself, October 27, 1986, when he spoke twice. In the opening greeting inside the Basilica of

Santa Maria degli Angeli he referred to the human quest for "the Absolute Being,"[6] glossing over the fact that the Buddhists and polytheists represented there do not believe in any one "Absolute Being." While the Pope again denied any "relativist" character in the planned activity,[7] nothing he said there suggested anything contrary to the view condemned by Pius XI in

Mortalium Animos. At the end of the day, after all representatives had listened to the others offering their respective prayers, the Pope spoke again, dedicating almost his entire discourse to the need for peace, and the means of achieving it. Again, nothing at all here suggested that some religions might be objectively something other than "more or less good and praiseworthy." [8]

All this is also true in regard to the third allocution referred to by my critic, that of the Wednesday general audience allocution of May 19, 1999. Indeed, on this occasion, John Paul II mentioned polytheistic worship only to

praise it, referring to "the traditional African religions, which constitute for many peoples a source of wisdom and life."[9] Does not this assertion suggest that these pagan cults are "more or less good and praiseworthy"? In similar vein, His Holiness continued by appealing to the new

Catechism -- but quite selectively, and in fact, with questionable accuracy. Referring to No. 843, he said: "In effect, every religion presents itself as a search for salvation, and proposes paths by which to attain it."[10] Readers may judge for themselves whether No. 843, which recognizes certain positive elements in "other religions," really says or implies that. But in any case one must wonder why, if the Pope had wished to show continuity between his teaching and that of his predecessors such as Pius XI, he did not also cite the very next article of the

Catechism, which echoes St. Paul's condemnation of pagan idolatry in Romans 1: "In their religious behavior, however, men also display the limits and errors that disfigure the image of God in them: 'Very often, deceived by the Evil One, men have become vain in their reasonings and have exchanged the truth of God for a lie, and served the creature rather than the Creator'" (

CCC No. 844, citing

Lumen Gentium No. 16)

In short, none of these papal interventions lends any support to the contention that the 1986 Assisi gathering, when understood correctly, was untarnished by the error Pius XI had condemned. On the contrary, it seems impossible to deny that they actually reinforce that error -- both by what they say and what they conspicuously fail to say. The scandal given is thus true and objective, not just "sandal of the weak bordering on Pharisaical scandal."

Similar comments could be made about Assisi II (2002). Far from saying anything against the error that "all religions are more or less good and praiseworthy," the Pontiff's own remarks and the official Vatican booklet setting out the day's proceeding tended, if anything, to communicate that error. The booklet speaks, for instance, of "the followers of the different religions, their hearts enlightened by the religious spirit which everywhere promotes fraternity among the world's peoples...."[11] The Pope himself declared: "In God's name may all religions bring upon earth justice and peace, forgiveness, life and love,"[12] and in his homily asserted that "true religious feeling" -- which in this context was clearly meant to include virtually any and every religion, including the pagan varieties represented among the Pope's listeners -- "is a wellspring of respect and harmony between peoples: ... the chief antidote to violence and conflict." [13]

Now, given these sorts of glowing claims about the life-giving, peacemaking elixir to be distilled from "all religions," and given that, in his discourses related to Assisi, His Holiness never expressed anything more than the very mildest reservations about even the crudest forms of paganism (and even then, going on to describe them as "a source of wisdom and life for many peoples"), how could any impartial listener or reader be expected to draw any conclusion

other than that John Paul II did indeed consider "all religions" to be "more or less good and praiseworthy"?

Let us return to the question of the late Holy Father's cause for canonization. As is well known, evidence is always required, as a condition for even beatification, that the Servant of God under consideration reached a

heroic level in all seven main virtues: four of them cardinal (prudence, justice, fortitude and temperance) and three of them theological (faith, hope and charity). If the conclusions I have come to about John Paul II and Assisi are correct, then I respectfully submit that they constitute weighty evidence:

first, that this well-beloved Pontiff, for all his many outstanding human and spiritual qualities, displayed a less than heroic level of

prudence, in an extremely important manner, by overriding the advice of numerous cardinals in order to convoke high-profile and hitherto unheard-of interreligious gatherings that were predictably bound to sow confusion among millions round the world regarding the unique salvific role of the Catholic religion: and

second, that the same Assisi gatherings, interpreted in the light of the Pope's own explanatory discourses, betrayed a decidedly less than heroic level in the still more fundamental virtue of

faith. For these data suggest very strongly that John Paul's well-known optimism regarding the boundless love and universal salvific will of God -- in itself something admirable, and indeed, linked to the related virtue of hope -- exceeded the limits of due proportion, so as to obscure, overshadow or minimize this Pontiff's faith in an article of revealed truth based on the very First Commandment and clearly taught in his own

Catechism (articles 844 and 2112): the truth that idolatry (in polytheistic, pantheistic, or any other forms) is an abomination that stands condemned by God, and thus merits condemnation by man. Especially by Christ's Vicar on earth.

(to be continued next issue)Notes

1. In this respect I have been less severe in my evaluation of Assisi than the highly respected Italian journalist Vitto Messori, who has published long (book-length) interviews with the then Cardinal Ratzinger and John Paul II himself. Messori did not hesitate to state publicly that the Assisi gatherings in effect promoted indifferentism and relativism. (Cf. CWNews briefs, February 5, 2002, cited in C. Ferrara & T. Woods, The Great Facade [Wyoming, Minnesota: Remnant Press, 2002], p. 213.)

2. Cf. Ferrara & Woods, op. cit., p. 84.

3. "Conocemos cuáles son los límites de esas religiones, pero eso no quita en absoluto que haya en ellas valores y cualidades religiosas, incluso insignes" (L'Osservatore Romano [weekly Spanish ed.], October 26, 1986, p. 3).

4. "... están llamados a contribuir al nacimiento de un mundo más humano, más justo más fraterno" (ibid).

5. "De este modo manifestamos nuestro respeto por la oración de los otros y por la actitud de los demás ante la Divinidad" (ibid).

6. "... el Ser Absolute" (L'Osservatore Romano [weekly Spanish ed.], November 2, 1986, p. 2).

7. Ibid., p. 1.

8. Ibid., p. 11.

9. "las religiones tradicionales africanas, que constituyen para muchos pueblos, una fuente de sabiduría y vida" (L'Osservatore Romano [weekly Spanish ed.], May 21, 1999, p. 3.

10. "En efecto, toda religión se presenta como una búsqueda de salvación y propone itinerarios para alcanzarla" (ibid).

11. Together For Peace (Vatican Press, 2002), p. 13.

12. Ibid., p. 19.

13. Complete text available on Vatican website.

[Father Brian Harrison, O.S., a convert to the Catholic faith from Presbyterianism, is a native of Australia. He earned his doctorate in Theology, summa cum laude, from the roman Athenaeum of the Holy Cross and is now an Associate Professor of Theology in the Pontifical Catholic University of Puerto Rico. He is a member of the Priestly Society of the Oblates of Wisdom. The present article, "John Paul II and Assisi: Reflections of a 'Devil's Advocate'" (Part I)," was originally published in Latin Mass: A Journal of Catholic Culture and Tradition (Advent/Christmas, 2005), pp. 6-10, and is reprinted here by permission of Latin Mass Magazine, 391 E. Virginia Terrace, Santa Paula, CA 93060.]

In the latest issue of Latin Mass magazine (Fall 2006), Editor Fr. James McLucas (right) relates two incidents that illustrate the problem:

In the latest issue of Latin Mass magazine (Fall 2006), Editor Fr. James McLucas (right) relates two incidents that illustrate the problem: I know of no problems that Latin rite bishops or priests have had with these. The Latin Church has also had different liturgical rites -- Carthusian (Carmelite and Dominican), Ambrosian, Mozarabic, the Braga rite, etc. I know of no problems that Latin rite bishops or priests have had with these. But softly speak the words "TRIDENTINE MASS" in the company of your local ordinary and his chancery priests, or, for that matter, in your local Novus Ordo parish, and you will induce an apoplectic response such as you would not begin to elicit if you had merely bitten the head off of a gerbil and swallowed it. Why is this, I wonder?

I know of no problems that Latin rite bishops or priests have had with these. The Latin Church has also had different liturgical rites -- Carthusian (Carmelite and Dominican), Ambrosian, Mozarabic, the Braga rite, etc. I know of no problems that Latin rite bishops or priests have had with these. But softly speak the words "TRIDENTINE MASS" in the company of your local ordinary and his chancery priests, or, for that matter, in your local Novus Ordo parish, and you will induce an apoplectic response such as you would not begin to elicit if you had merely bitten the head off of a gerbil and swallowed it. Why is this, I wonder?

remarks how Ratzinger called attention to the "deep christological continuity" with the liturgical past when he evoked "the real interior act" of Jesus' "Yes" to the Father on the Cross that takes all time into his heart (pp. 56-57). "This is the 'event of institution' that assures organic continuity down the ages," says Fessio. Commenting on the Novus Ordo, he writes:

remarks how Ratzinger called attention to the "deep christological continuity" with the liturgical past when he evoked "the real interior act" of Jesus' "Yes" to the Father on the Cross that takes all time into his heart (pp. 56-57). "This is the 'event of institution' that assures organic continuity down the ages," says Fessio. Commenting on the Novus Ordo, he writes:  namely Martin Mosebach's The Heresy of Formlessness: The Roman Liturgy and Its Enemy, translated by Graham Harrison (Ignatius Press, 2003), and bearing the inscription "For Robert Spaemann, in gratitude." Mosebach sees no hope but for a restoration of the traditional Latin Mass, and Fessio, of course, as a partisan of the "reform of the reform," does not agree with him. Yet Fessio saw fit to publish Mosebach's book because of his intuitively formidable and incisive critique of the jarring break with tradition in the contemporary forms of the liturgy. Hat tip to Fr. Fessio! But here's the kicker -- look at what Mosebach writes about the Novus Ordo!

namely Martin Mosebach's The Heresy of Formlessness: The Roman Liturgy and Its Enemy, translated by Graham Harrison (Ignatius Press, 2003), and bearing the inscription "For Robert Spaemann, in gratitude." Mosebach sees no hope but for a restoration of the traditional Latin Mass, and Fessio, of course, as a partisan of the "reform of the reform," does not agree with him. Yet Fessio saw fit to publish Mosebach's book because of his intuitively formidable and incisive critique of the jarring break with tradition in the contemporary forms of the liturgy. Hat tip to Fr. Fessio! But here's the kicker -- look at what Mosebach writes about the Novus Ordo!  my discovery of Kansas City's

my discovery of Kansas City's  Another joy of this trip, rather coincidental with the first, was visiting my son, Benjamin, and his family at Benedictine College and seeing him ensconced in a supportive community in that place. I was impressed that a college of some 1200 full time students could mount a faculty of five or six each in the departments of theology and philosophy with nine hour course requirements of all students in each of those two areas; and a Freshman seminar course devoted to study of the college mission! Heavens! How do they do it! Haven't they heard of "market forces"? Aren't they aware that students aren't interested in such things anymore? What happened to their market consultants? Faculty members told me that Benedictine College has been collecting statistics on what students report as their reasons for selecting Benedictine College. You know what the number one reason is? It's their clear Catholic commitment. Huzzah! Put that in your pipes and smoke it, all you market consultants and educational demographic experts!

Another joy of this trip, rather coincidental with the first, was visiting my son, Benjamin, and his family at Benedictine College and seeing him ensconced in a supportive community in that place. I was impressed that a college of some 1200 full time students could mount a faculty of five or six each in the departments of theology and philosophy with nine hour course requirements of all students in each of those two areas; and a Freshman seminar course devoted to study of the college mission! Heavens! How do they do it! Haven't they heard of "market forces"? Aren't they aware that students aren't interested in such things anymore? What happened to their market consultants? Faculty members told me that Benedictine College has been collecting statistics on what students report as their reasons for selecting Benedictine College. You know what the number one reason is? It's their clear Catholic commitment. Huzzah! Put that in your pipes and smoke it, all you market consultants and educational demographic experts! Susan Treacy, from Ave Maria University, offered an interesting presentation on how Benedict XVI's vision for sacred music might sound in an American parish. That, essentially, was the subtitle of her talk, entitled "The Music of Cosmic Liturgy." In her presentation, she played some CD recordings of a dialogical, sung Mass, with the people antiphonally responding to the priest, who takes the lead. She highlighted the Ordinaries and, particularly, the Propers, which, she said, have been altogether underrated for the aesthetic and spiritual role they can potentially play in liturgy if placed in the appropriate musical settings. If the audio recordings, performed by a Dutch group, are any indication of what could realistically be said to lay in our future, I would be hopeful. The settings are reverent and beautiful and lift one out of the mundane and banal "environment of art and Catholic worship" we now too often suffer.

Susan Treacy, from Ave Maria University, offered an interesting presentation on how Benedict XVI's vision for sacred music might sound in an American parish. That, essentially, was the subtitle of her talk, entitled "The Music of Cosmic Liturgy." In her presentation, she played some CD recordings of a dialogical, sung Mass, with the people antiphonally responding to the priest, who takes the lead. She highlighted the Ordinaries and, particularly, the Propers, which, she said, have been altogether underrated for the aesthetic and spiritual role they can potentially play in liturgy if placed in the appropriate musical settings. If the audio recordings, performed by a Dutch group, are any indication of what could realistically be said to lay in our future, I would be hopeful. The settings are reverent and beautiful and lift one out of the mundane and banal "environment of art and Catholic worship" we now too often suffer. Fr. Samuel Weber, from Wake Forest University, actually put some of these ideas into effect in a sort of workship in which he taught the conference participants to chant some antiphonal plainsong Mass settings that he had arranged and printed for the occasion in a booklet for us entitled, Chants for the Order of Mass (2006). Weber, who previously spoke at Lenoir-Rhyne College at one of our annual Aquinas-Luther Conferences, has been working for some years arranging English verse in plainsong settings -- no easy feat. But the results were and are, to say the least, encouraging. While English does not lend itself to chant as readily as naturally as Latin, as anyone who understands chant knows, Weber has done a remarkable job of implementing the cadences and inflections of English verse in conformity with the principles of chant to yield a fine result. Weber is a consumate teacher, energetic, inspiring, and effective. If Weber's workshop is any indication, chant is not that difficult to learn. A willing congregation ('willing' being the operative word) could be taught to chant some of the simpler Mass settings with minimal effort. If the Novus Ordo could be rendered in plainsong, I think many of it's extraneous problems would disappear. Anyone interested in subscribing to his plainsong settings for weekly Sunday Masses, may contact him, he says, at the following address: Rev. Samuel F. Weber, O.S.B., Box 7719, Wake Forest University, Winston Salem, NC 27109-7719 (or

Fr. Samuel Weber, from Wake Forest University, actually put some of these ideas into effect in a sort of workship in which he taught the conference participants to chant some antiphonal plainsong Mass settings that he had arranged and printed for the occasion in a booklet for us entitled, Chants for the Order of Mass (2006). Weber, who previously spoke at Lenoir-Rhyne College at one of our annual Aquinas-Luther Conferences, has been working for some years arranging English verse in plainsong settings -- no easy feat. But the results were and are, to say the least, encouraging. While English does not lend itself to chant as readily as naturally as Latin, as anyone who understands chant knows, Weber has done a remarkable job of implementing the cadences and inflections of English verse in conformity with the principles of chant to yield a fine result. Weber is a consumate teacher, energetic, inspiring, and effective. If Weber's workshop is any indication, chant is not that difficult to learn. A willing congregation ('willing' being the operative word) could be taught to chant some of the simpler Mass settings with minimal effort. If the Novus Ordo could be rendered in plainsong, I think many of it's extraneous problems would disappear. Anyone interested in subscribing to his plainsong settings for weekly Sunday Masses, may contact him, he says, at the following address: Rev. Samuel F. Weber, O.S.B., Box 7719, Wake Forest University, Winston Salem, NC 27109-7719 (or  Denis NcNamara, from the Liturgical Institute in Chicago, talked about religious art. He drew a distinction between three kinds of art: (1) liturgical, (2) devotional, and (3) historical art. With examples drawn especially (but not exclusively) from the Orthodox tradition, he showed how liturgical art facilitates worship by elevating us out of the temporal into the timeless realm of the eternal. Devotional art is exemplified by the mail order statues, for example, of the Sacred Heart or the Blessed Virgin one used to see in the side altars of traditional churches and sometimes still sees in churches today. They facilitate personal devotion, but not necessarily liturgy. Historical art is art that depicts historical scenes with varying degrees of historical realism, such as the nativity, crucifixion, or other biblical scenes that may be good religious art but don't necessarily facilitate liturgy either. Some good theory along these lines.

Denis NcNamara, from the Liturgical Institute in Chicago, talked about religious art. He drew a distinction between three kinds of art: (1) liturgical, (2) devotional, and (3) historical art. With examples drawn especially (but not exclusively) from the Orthodox tradition, he showed how liturgical art facilitates worship by elevating us out of the temporal into the timeless realm of the eternal. Devotional art is exemplified by the mail order statues, for example, of the Sacred Heart or the Blessed Virgin one used to see in the side altars of traditional churches and sometimes still sees in churches today. They facilitate personal devotion, but not necessarily liturgy. Historical art is art that depicts historical scenes with varying degrees of historical realism, such as the nativity, crucifixion, or other biblical scenes that may be good religious art but don't necessarily facilitate liturgy either. Some good theory along these lines. Duncan Stroik, from Notre Dame School of Architecture, gave an interesting talk in which he wondered aloud how Catholic churches and Cathedrals ever used to be built without the help of Liturgical Design Consultants! (You know the significant difference between Liturgical Experts and Terrorists, right? Right: you can negotiate with terrorists.) He also offered a substantial discussion of six aspects of church buildings in terms of their (1) sacred space, (2) liturgical function per se, (3) sacramental dimension, (4) liturgical elements, (5) devotional purposes, and (6) iconographic and symbolic functions. Very interesting.

Duncan Stroik, from Notre Dame School of Architecture, gave an interesting talk in which he wondered aloud how Catholic churches and Cathedrals ever used to be built without the help of Liturgical Design Consultants! (You know the significant difference between Liturgical Experts and Terrorists, right? Right: you can negotiate with terrorists.) He also offered a substantial discussion of six aspects of church buildings in terms of their (1) sacred space, (2) liturgical function per se, (3) sacramental dimension, (4) liturgical elements, (5) devotional purposes, and (6) iconographic and symbolic functions. Very interesting. Magdi Allam is a leading Muslim commentator in Italy. He has written a major editorial for an Italian national newspaper, Corriere della Sera. The editorial (in the original Italian) is entitled "

Magdi Allam is a leading Muslim commentator in Italy. He has written a major editorial for an Italian national newspaper, Corriere della Sera. The editorial (in the original Italian) is entitled " "In Regensburg, the pope offered as terrain for dialogue between Christians and Muslims 'acting according to reason.' But the Islamic world has attacked him, distorting his thought, confirming by this that the rejection of reason brings intolerance and violence along with it." Thus writes Sandro Magister, at

"In Regensburg, the pope offered as terrain for dialogue between Christians and Muslims 'acting according to reason.' But the Islamic world has attacked him, distorting his thought, confirming by this that the rejection of reason brings intolerance and violence along with it." Thus writes Sandro Magister, at  In the current issue of the NOR, again in a New Oxford Note -- this one entitled "

In the current issue of the NOR, again in a New Oxford Note -- this one entitled " Eugene Judy, a professional genealogical researcher, discovered that Hillary Clinton's great-great uncle, Remus Rodham, a fellow lacking in character, was hanged for horse stealing and train robbery in Montana in 1889. The only known photograph of Remus shows him standing on the gallows.

Eugene Judy, a professional genealogical researcher, discovered that Hillary Clinton's great-great uncle, Remus Rodham, a fellow lacking in character, was hanged for horse stealing and train robbery in Montana in 1889. The only known photograph of Remus shows him standing on the gallows.

Now that the cause for beatification of the late Holy Father John Paul II has been officially opened by the successor in the See of Peter, an open, public and honest discussion of his long and epoch-making pontificate, marked by a calm and serious evaluation of its possible weaknesses as well as its undoubted strengths, has become not only opportune but also necessary. For the long-standing tradition of the Church is that no Servant of God may be raised to the honors of the altar before both sides of the question -- that is, testimonies both for and against his or her sanctity -- are first heard and taken into due consideration.

Now that the cause for beatification of the late Holy Father John Paul II has been officially opened by the successor in the See of Peter, an open, public and honest discussion of his long and epoch-making pontificate, marked by a calm and serious evaluation of its possible weaknesses as well as its undoubted strengths, has become not only opportune but also necessary. For the long-standing tradition of the Church is that no Servant of God may be raised to the honors of the altar before both sides of the question -- that is, testimonies both for and against his or her sanctity -- are first heard and taken into due consideration. Of course, a number of authoritative post-conciliar Church documents, regarding Assisi and other ecumenical and interreligious activities, clearly assert that such forms of dialogue and collaboration do not involve, and are not intended to imply, such errors as indifferentism, syncretism, or relativism. (1) Syncretism is the mixing together of elements from Christianity with those of non-Christian religions, or a reductionist search for unity through a 'lowest common denominator' approach. (2) Indifferentism is the view that any given religion is basically just as good (or bad) as any other. And (3) relativism holds (along very similar lines to indifferentism) that there are no absolute or universal religious truths, so that one religion can be true or right for one culture or historical period, while other religions (or no religion at all) may be right for other cultures or periods.

Of course, a number of authoritative post-conciliar Church documents, regarding Assisi and other ecumenical and interreligious activities, clearly assert that such forms of dialogue and collaboration do not involve, and are not intended to imply, such errors as indifferentism, syncretism, or relativism. (1) Syncretism is the mixing together of elements from Christianity with those of non-Christian religions, or a reductionist search for unity through a 'lowest common denominator' approach. (2) Indifferentism is the view that any given religion is basically just as good (or bad) as any other. And (3) relativism holds (along very similar lines to indifferentism) that there are no absolute or universal religious truths, so that one religion can be true or right for one culture or historical period, while other religions (or no religion at all) may be right for other cultures or periods. All this is also true in regard to the third allocution referred to by my critic, that of the Wednesday general audience allocution of May 19, 1999. Indeed, on this occasion, John Paul II mentioned polytheistic worship only to praise it, referring to "the traditional African religions, which constitute for many peoples a source of wisdom and life."[9] Does not this assertion suggest that these pagan cults are "more or less good and praiseworthy"? In similar vein, His Holiness continued by appealing to the new Catechism -- but quite selectively, and in fact, with questionable accuracy. Referring to No. 843, he said: "In effect, every religion presents itself as a search for salvation, and proposes paths by which to attain it."[10] Readers may judge for themselves whether No. 843, which recognizes certain positive elements in "other religions," really says or implies that. But in any case one must wonder why, if the Pope had wished to show continuity between his teaching and that of his predecessors such as Pius XI, he did not also cite the very next article of the Catechism, which echoes St. Paul's condemnation of pagan idolatry in Romans 1: "In their religious behavior, however, men also display the limits and errors that disfigure the image of God in them: 'Very often, deceived by the Evil One, men have become vain in their reasonings and have exchanged the truth of God for a lie, and served the creature rather than the Creator'" (CCC No. 844, citing Lumen Gentium No. 16)

All this is also true in regard to the third allocution referred to by my critic, that of the Wednesday general audience allocution of May 19, 1999. Indeed, on this occasion, John Paul II mentioned polytheistic worship only to praise it, referring to "the traditional African religions, which constitute for many peoples a source of wisdom and life."[9] Does not this assertion suggest that these pagan cults are "more or less good and praiseworthy"? In similar vein, His Holiness continued by appealing to the new Catechism -- but quite selectively, and in fact, with questionable accuracy. Referring to No. 843, he said: "In effect, every religion presents itself as a search for salvation, and proposes paths by which to attain it."[10] Readers may judge for themselves whether No. 843, which recognizes certain positive elements in "other religions," really says or implies that. But in any case one must wonder why, if the Pope had wished to show continuity between his teaching and that of his predecessors such as Pius XI, he did not also cite the very next article of the Catechism, which echoes St. Paul's condemnation of pagan idolatry in Romans 1: "In their religious behavior, however, men also display the limits and errors that disfigure the image of God in them: 'Very often, deceived by the Evil One, men have become vain in their reasonings and have exchanged the truth of God for a lie, and served the creature rather than the Creator'" (CCC No. 844, citing Lumen Gentium No. 16)